The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane

The Adventures of Robert E. Howard's First and Most Complex Character

“For man’s only weapon is courage that flinches not from the gates of Hell itself, and against such not even the legions of Hell can stand.”-

-‘Skulls In the Stars’, Robert E. Howard

For all of contemporary media’s farcical assertions that pulp is some branch of the exploitation genre, a cursory viewing of the works of Raymond Chandler or any old west pulps goes a long way to dispelling this myth. While certain heroes like Lieber’s Fahfrd and the Grey Mouser or Moorcock’s Elric of Melnibone definitely fit the mold of the antihero (and in Elric’s case even border on villain status), most popular scions of classic pulp include great, morally binary heroes like The Shadow, Doc Savage, Zorro, Philip Marlowe, Tarzan, The Spider, or The Avenger. These heroes are starkly defined by a clear, black and white morality often the result of needing to fit a typical, villain of the week storyline. It’s much easier to do that if you don’t establish a character as a morally-grey, wishy washy rooftop brooder unless you’re establishing a tragic character like Elric doomed to fall by his own personal deficiencies. I’d argue that Conan isn’t even as morally grey as others might assert, given that the titular hero actually operates with a form of morality that seems incommensurate with his barbarian nature—such as his reluctance to harm or slay women (even sorceresses). In fact, Conan never preys upon the innocent and vulnerable, but on fellow mercenaries, pirates, sorcerers, witches, and corrupt bureaucrats. Even when he conquered his future kingdom of Aquilonia, he did so as a liberator from the tyrant that ruled at the time.

However, Howard’s first character is, in his own way, even more pulp than Conan. For while Conan’s core thematic conceit is unfettered freedom, Howard’s seminal, puritan swashbuckler, Solomon Kane, is an unflinching, devout agent of inviolable justice. While Conan evokes the noble savage concept in stark contrast and critique of the savagery inherent to so-called “civilization”, Kane functions as a sort of wayward knight lost in an age where chivalry is dead and people live in fear of forces both mortal and ethereal. He bears the same inherently savage impulses of Conan or Kull (his ‘pagan’ nature, as it were), but channels them into a righteous sense of justice, whereupon he visits that savagery and fury upon those who’d prey upon the weak. In his own way, Kane’s dour appearance equally belies his darker nature and his religious devotion, while his long, slender rapier (in stark contrast to the hefty swords, axes, and clubs of Conan) emphasizes the way in which he channels both those impulses and his faith into a strong sense of justice and a righteous fury which he inflicts upon evildoers. While Conan obeys his impulses and always expressed uncertainty as to the nature of gods and fate and his place in it all, hacking his way through any that stand in his way, Kane is a man driven by a strong sense of justice and focused through devout adherence to his religious principles.

“He never sought to analyze his motives and he never wavered, once his mind was made up. Though he always acted on impulse, he firmly believed that all his actions were governed by cold and logical reasonings. He was a man born out of his time - a strange blending of Puritan and Cavalier, with a touch of the ancient philosopher, and more than a touch of the pagan, though the last assertion would have shocked him unspeakably. An atavist of the days of blind chivalry he was, a knight errant in the sombre clothes of a fanatic. A hunger in his soul drove him on and on, an urge to right all wrongs, protect all weaker things, avenge all crimes against right and justice. Wayward and restless as the wind, he was consistent in only one respect - he was true to his ideals of justice and right. Such was Solomon Kane.”-

- ‘The Moon of Skulls’, Howard

So pronounced are Kane’s faith and sense of justice that he won’t indulge in doubts or allow himself time to brood and mope over the sorry state of the world or his sense of purpose. He doesn’t need a personal connection or sense of kinship, race, culture, or even religion in order to seek justice for someone. Indeed, few people, even of faith, believe or act like Solomon Kane. He didn’t choose to protect the innocent because a mugger killed his parents in an alleyway or because he lost his girlfriend or some other trite, overused tragic backstory. He does so for the simple reason that it’s the right thing to do.

This point is emphasized right off the bat in Kane’s debut story, ‘Red Shadows’, wherein he happens upon a dying girl who reveals she was raped and mortally wounded by the pirate Le Loup. He’s never known nor ever will know the girl, nor did he have anything to do with her decimated village. Yet as she dies in his arms, he vows to slay her killers at all costs.

“Suddenly the slim form went limp. The man eased her to the earth, and touched her brow lightly. ‘Dead!’ he muttered. Slowly he rose, mechanically wiping his hands upon his cloak. A dark scowl had settled on his somber brow. Yet he made no wild, reckless vow, swore no oath by saints or devils. ‘Men shall die for this,’ he said coldly.”-

-‘Red Shadows’, Howard

From that moment, he hunts Le Loup for years across Europe and all the way to Africa all to avenge an innocent stranger.

“The air was tense for an instant; then the Wolf relaxed elaborately. ‘Who was the girl?’ he asked idly. ‘Your wife?’ ‘I never saw her before,’ answered Kane. ‘Nom d'un nom!’ swore the bandit. ‘What sort of a man are you, Monsieur, who takes up a feud of this sort merely to avenge a wench unknown to you?’ ‘That, sir, is my own affair; it is sufficient that I do so.’ Kane could not have explained, even to himself, nor did he ever seek an explanation within himself. A true fanatic, his promptings were reasons enough for his actions.”-

-‘Red Shadows’, Howard

Furthermore, while critics make fascicle, arrogant arguments about Howard’s less than enlightened views on race and choose to focus on that element in particular, Howard often demonstrated more progressive views on race than his contemporaries in many writings including some of the Kane stories. While many like to point out the offensive descriptions of Africans in certain stories, it’s necessary to point out that these unflattering descriptions are only present when a black character is cast as a villain. When they’re allies, he describes them quite flatteringly, and in at least three stories, Kane fights on behalf of certain Africans he encounters, most especially in ‘Wings in the Night’, which I’ll talk about later, and his only recurring ally is an African juju man named N’Longa.

In fact, that’s all a part of Kane’s character development. He starts out with the typical, discriminatory racial attitudes towards Africans in early stories like ‘Red Shadows’ and ‘The Moon of Skulls’, but gradually comes to realize that they are human beings like himself with their own value. We first see an example of this changing attitude when he saves an African girl from a lion in, ‘Hills of the Dead’.

“She whimpered a little. ‘Are you not a god?’ ‘No, Zunna. I am only a man, though the color of my skin is not as yours.’”-

-‘Hills of the Dead’, Howard

Not to mention, the unflattering descriptions just as often stretch to white characters, proving that their purpose was to emphasize the characters’ villainy—not make a racial statement.

“This face was lean, hawk-like and cruel. A cocked hat topped the narrow high forehead, pulled low over sparse, black brows, but not too low to hide the gay bandana beneath. In the shadow of the hat a pair of cold grey eyes danced recklessly, with changing sparks of light and shadow. A knife-bridged beak of a nose hooked over a thin gash of a mouth, and the cruel upper lip was adorned with long drooping mustachios, much like those worn by the Manchu Mandarins.”-

-‘The Blue Flame of Vengeance’, Howard

“But where Solomon was dark, Jeremy Hawk was blond. Now he was burned to light bronze by the sun, and his tangled yellow locks fell over his high narrow forehead. His jaw, masked by a yellow stubble, was lean and aggressive, and his thin gash of a mouth was cruel. His grey eyes were gleaming and restless, full of wild glitterings and shifting lights. His nose was thin and aquiline and his whole face was that of a bird of prey.”-

-‘Hawk of Basti’, Howard

Kane further demonstrates his newfound care towards Africans and extends his sense of justice to include them in, ‘The Footfalls Within’. The core plot revolves around Kane tracking down Muslim slavers (made up of both Arabs and Moors) in order to free their black slaves, and he only gives away his position when he impulsively saves a slave girl from being murdered by one of the slavers. This impulsive act also goes further to demonstrate the aforementioned instinctual sense of justice that so defines this character.

“Kane, sick with horror, realized, too, that the girl's was to be no easy death. He knew what the tall Moslem intended to do, as he stooped over her with a keen dagger such as the Arabs used for skinning game. Madness overcame the Englishman. He valued his own life little; he had risked it without thought for the sake of a negro baby or a small animal. Yet he would not have premeditatedly thrown away his one hope of succouring the wretches in the train. But he acted without conscious thought. A pistol was smoking in his hand and the tall butcher was down in the dust of the trail with his brains oozing out, before Kane realized what he had done. He was almost as astonished as the Arabs, who stood frozen for a moment and then burst into a medley of yells.”-

-‘Footfalls Within’, Howard

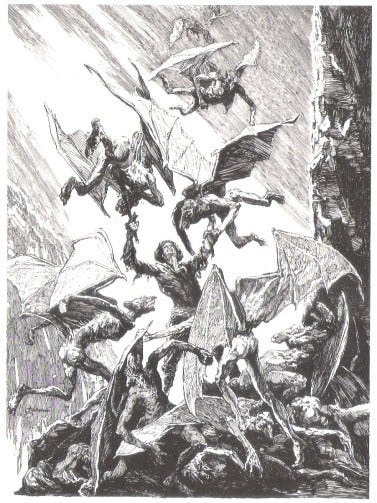

However, Kane’s staunch moral code and consistent religiosity don’t mean that he never encounters moral quandaries or even occasionally doubts his faith. Quite the contrary, as even his rigid, puritanical exterior is shaken to its core by the cruelty, avarice, and demonic powers he encounters on the course of his journeys. The most glaring example of this comes from the story, ‘Wings in the Night’, wherein Kane is nearly killed by a mysterious, winged beast and subsequently nursed back to health by a kindly African tribe. The frightened tribesmen tell him how the winged beasts have preyed upon them for years requiring human sacrifices to sate their sadistic bloodlust. Heeding their pleas for help, Kane takes on the task of defending them, but sadly fails, resulting in the death of the whole tribe he’d come to know and regard as friends. In the aftermath of the slaughter, despair overcomes him, and he uncharacteristically raves in a moment of blind fury and blasphemy in the chapter aptly titled, ‘The Madness of Solomon’.

“Kane looked at the shambles that had been Bogonda, and he looked at the death mask of Goru. And he lifted his clenched fists above his head, and with glaring eyes raised and writhing lips flecked with froth, he cursed the sky and the earth and the spheres above and below. He cursed the cold stars, the blazing sun, the mocking moon, and the whisper of the wind. He cursed all fates and destinies, all that he had loved or hated, the silent cities beneath the seas, the past ages and the future aeons. In one soul-shaking burst of blasphemy he cursed the gods and devils who make mankind their sport, and he cursed Man who lives blindly on and blindly offers his back to the iron-hoofed feet of his gods.”-

-‘Wings In the Night’, Howard

After briefly succumbing to his fury, Kane traps and massacres every one of the winged terrors in bloody vengeance. Then, with the symbolic coming of the dawn, he reconciles the tragedy of Bogonda and reaffirms both his holy mission and his faith in God.

“Smoke curled upward into the morning sky, and the roaring of foraging lions shook the plateau. Slowly, like light breaking through mists, sanity returned to him. ‘The light of God's morning enters even into dark and lonesome lands,’ said Solomon Kane sombrely. ‘Evil rules in the waste lands of the earth, but even evil may come to an end. Dawn follows midnight and even in this lost land the shadows shrink. Strange are Thy ways, oh God of my people, and who am I to question Thy wisdom? My feet have fallen in evil ways but Thou hast brought me forth scatheless and hast made me a scourge for the Powers of Evil. Over the souls of men spread the condor wings of colossal monsters and all manner of evil things prey upon the heart and soul and body of Man. Yet it may be in some far day the shadows shall fade and the Prince of Darkness be chained forever in his hell. And till then mankind can but stand up stoutly to the monsters in his own heart and without, and with the aid of God he may yet triumph.’"

-‘Wings In the Night’, Howard

While Kane does momentarily doubt his faith and descends into fury, despair, and blasphemy at his failure to protect the people who he’d vowed to save, he doesn’t become a typical, cynical, relativist, modernist antihero. When the smoke clears and the dawn breaks, he recognizes and accepts that the world is a cruel place fraught with sin and every evil, and that only the light of God can save the innocent who suffer because of it. He recognizes his own, mortal lack of understanding, the evil nature of man, and the demonic beings that beset humanity, and he realizes that only through courage and faith in God can light and justice be brought to the world. While Kane now better understands the darkness and injustice of the world, it only serves to reaffirm his mission rather than change it and to strengthen his faith and reliance on God after recognizing his own shortcomings.

Yet, while Kane’s religiosity and sense of justice are major themes of the stories, don’t mistakenly expect something preachy or dogmatic. While the morality and religion that motivate Solomon Kane are central themes of most of his stories, they more so are demonstrated through his actions with the exception of the sermons/monologues he gives at the end of ‘Wings in the Night’ and ‘Moon of Skulls’ (the former of which is practically a full-on sermon). You only need a passage or two to remind you of his religiosity, and then the rest of the story is concerned with putting those ethics into action. Nor do all of his tales involve magic and the supernatural, given there are several stories and poems of Kane fighting pirates and brigands of all sorts, such as in ‘The Blue Flame of Vengeance’. Some are straightforward short horror stories, like ‘The Right Hand of Doom’ or ‘The Rattle of Bones’.

‘Big deal,’ some might say. ‘Who cares if Kane was the first. He wasn’t anywhere near as influential as Conan.’

Au contraire, mon frere. Solomon Kane wasn’t just a lesser cousin of the almighty Conan—he was Howard’s first success. Even when Howard struck gold with Conan in his debut story Red Nails, he piggybacked off the success of Kane to do so.

“Nearly four years ago, WEIRD TALES published a story called ‘The Phoenix on the Sword,’ built around a barbarian adventurer named Conan, who had become king of a country by sheer force of valor and brute strength. The author of that story was Robert E. Howard, who was already a favorite with the readers of this magazine for his stories of Solomon Kane, the dour English Puritan and redresser of wrongs.”-

-Intro. Red Nails, Weird Tales, Vol. 28, Iss. 1

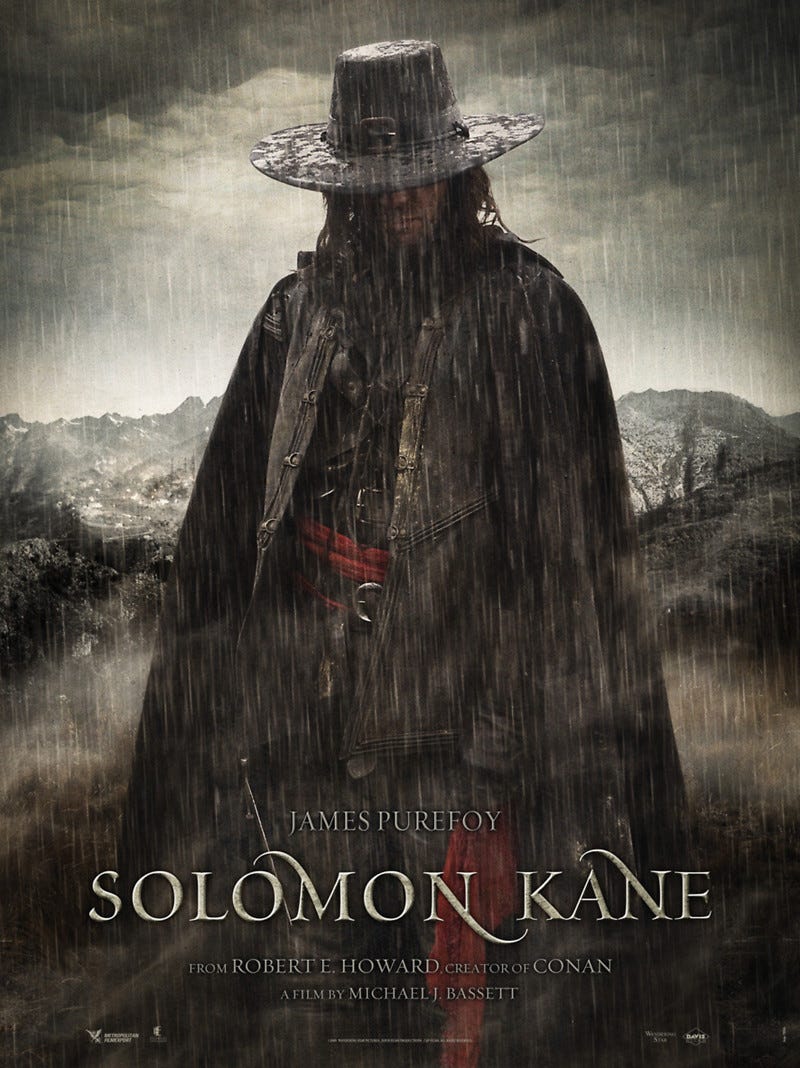

Those who read my previous article might recall I demonstrated that while Solomon Kane has declined in popularity in recent years, his influence on pop culture is immutable. One only need look at characters like Vampire Hunter D, Chakan the Foreverman, or Van Helsing to get an idea of the now common supernatural bounty hunter archetype that look suspiciously similar to Kane. Heck, the entire supernatural bounty hunter/monster slayer archetype owes itself to Kane! Just look at Hellboy, Blade, Jonah Hex, Constantine, Castlevania, Bloodborne, Goblin Slayer, or Berserk! Even fellow pulp icons like Zorro owe a debt to Kane. Kane continued to endure through the 90s and early 2000s in comic book adaptations from Marvel’s Solomon Kane miniseries, to the various Darkhorse Comics adaptations, to even a 1994 crossover with Conan in ‘The Savage Sword of Conan’ magazine. Then, in 2009, he made a long overdue leap to the silver screen in the self titled film featuring the criminally underrated talents of James Purefoy.

Sadly, despite its initial European release in 2009, the film was delayed in its official, American release until 2012. The film lived in the shadow of the revolutionary Lord of the Rings film trilogy and was somewhat hampered by a modest budget and receiving unfavorable comparisons to a previous box office bomb, ‘Van Helsing’, which was itself a Solomon Kane ripoff. The plot was also criticized for its formulaic nature, which has got to be a distance record for furthest from the point, given Kane is a PULP CHARACTER, and pulps are by nature FORMULAIC, just like every action movie in existence! Complaining about a pulp adaptation being formulaic is like complaining about capes in a superhero flick. What did you honestly expect? But I digress.

The film itself was caught in the unfortunate early 2000s trend (courtesy of Nolan’s ‘Batman Begins’) whereby we constantly feel the need to start a franchise with a character origin story whether the character in question has one or not. As a consequence, M.J. Basset created the first in what he’d hoped to be a three-film cycle wherein he cobbled together an unnecessary origin story for Kane whole-cloth rather than merely adapt one or more of the original stories. As a result, Purefoy’s Kane doesn’t fully feel like Kane until literally the final frames of the film, when he rides off into the distance and closes the film with an internal monologue affirming his newfound vocation.

“The demon is gone, banished to the shadows along with the sorcerer who had cursed us all. But evil is not so easily defeated, and I know I will have to fight again. I am a very different man now. Through all of my travels, all the things I've seen and all the things I've done, I have found my purpose. There was a time when the world was plunging into darkness. A time of witchcraft and sorcery, when no one stood against evil. That time... is over.”-

-Solomon Kane, 2009

Solomon Kane is Howard’s most complex character, and one brimming with far more potential than his barbarian successor. While Conan is largely a one note character (albeit an awesome entertaining one), Kane is a character defined by his moral and spiritual struggles as he strives to avenge the innocent, punish the guilty, and protect all weaker things. Yet we cheer for him and thrill at his every exploit because he overcomes those struggles and maintains his heroic persona throughout. He’s inspiring because his experiences only intensify his character, and his character and personality are two major reasons we follow his adventures in the first place.

The people who call Kane a ‘shallow character’ largely do so because he doesn’t run around in spandex, brood on rainswept rooftops, or cry and moan about his sorry state of existence. Solomon Kane is that rare breed of character that knows all he needs to know about who he is and what his purpose in life is. He doesn’t nurse doubts because he needs to act and think quickly, and that every moment he hesitates costs another’s life and allows the wicked to succeed. He’s not an archetype for us to see ourselves in; he’s an archetype for the kind of person we aspire to be. He’s flawed as all men are, but his flaws aren’t glorified. Rather, they are acknowledged, and part of the enjoyment is seeing him overcome those flaws to do what’s right.

Raymond Chandler once wrote his philosophy of a hero in ‘The Simple Art of Murder’, and it almost fits Kane to a ‘t’:

“…down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid. He is the hero; he is everything. He must be a complete man and a common man and yet an unusual man. He must be, to use a rather weathered phrase, a man of honor—by instinct, by inevitability, without thought of it, and certainly without saying it. He must be the best man in his world and a good enough man for any world…He will take no man’s money dishonestly and no man’s insolence without a due and dispassionate revenge. He is a lonely man and his pride is that you will treat him as a proud man or be very sorry you ever saw him…The story is this man’s adventure in search of a hidden truth, and it would be no adventure if it did not happen to a man fit for adventure…If there were enough like him, the world would be a very safe place to live in, without becoming too dull to be worth living in.”-

-Raymond Chandler

Howard, in fact, writes a similar passage to describe the motivation and mindset of Kane in ‘The Moon of Skulls’.

“He was a man born out of his time—a strange blending of Puritan and Cavalier, with a touch of the ancient philosopher, and more than a touch of the pagan, though the last assertion would’ve shocked him unspeakably. An atavist of the days of blind chivalry he was, a knight errant in the somber clothes of a fanatic. A hunger in his soul drove him on and on, an urge to right all wrongs, protect all weaker things, avenge all crimes against right and justice. Wayward and restless as the wind, he was consistent in only one respect—he was true to his ideals of justice and right. Such was Solomon Kane.”-

-‘The Moon of Skulls’, Howard

Kane is not only a flawed man, but in some ways a contradictory one, given that he even chooses to take up his sword in bloody retribution against evil doers. After all, he’s a puritan, and puritans were generally pacifists by nature and engaged mostly in reluctant participation in any war other than perhaps the Crusades. The stories occasionally go so far as to call into question not Kane’s genuine religiosity, but his staunch adherence to Puritanism. This’s all part and parcel of what makes Kane a fascinating character—the strangely incongruous aspects of his character and persona allow for fascinating internal conflict and paint a unique kind of supernatural crusader.

Yet almost as much a consistent theme as Kane’s sense of justice is his wayward nature. Solomon Kane is eternally cursed with wanderlust which takes his endless crusade all across the world in search of grand adventure and infernal abominations to slay. Yet he gains no pleasure from combat like Conan as repeatedly stated in stories like ‘Red Shadows’.

“Kane mechanically cleansed his sword on his tattered garments. The trail ended here, and Kane was conscious of a strange feeling of futility. He always felt that after he had killed a foe. Somehow it always seemed that no real good had been wrought; as if the foe had, after all, escaped his just vengeance.”-

-‘Red Shadows’, Howard

In fact, part of what drives his endless crusade is his search for satisfaction—the sense that he’s finally made a difference and achieved his mission. Yet the end of nearly every conflict leaves him with a sense of emptiness and futility because he knows there are always millions of evildoers still getting their way and millions of other innocents who suffer. Yet rather than throw his hands up and give up in desperation, he resigns himself to continue as an agent of God’s justice for the rest of his life, for only that mission gives him a sense of purpose. The sad result is that he can never put down roots. In this sense, Kane is a tragic hero eternally driven by a desire for justice, but eternally cursed with the feeling that he can never do enough and must, essentially, make penance for that fact by devoting his whole life to his crusade. For every person he saves it only reminds him of the millions of others he hasn’t saved.

“‘I am a landless man…I come out of the sunset and into the sunrise I go, wherever the Lord doth guide my feet. I seek—my soul’s salvation, mayhap. I came, following a trail of vengeance. Now I must leave you…My work here is done; the long red trail has ended. The man of blood is dead. But there be other men of blood, and other trails of revenge and retribution. I work the will of God. While evil flourishes and wrongs grow rank, while men are persecuted and women wronged, while weak things, human or animal, are maltreated, there is no rest for me beneath the skies, nor peace at any board or bed. Farewell!”-

-‘The Blue Flame of Vengeance’, Howard

Solomon Kane is essentially the prototype for what would be the American creation of superheroes, and I would argue that what has caused superheroes to fall to such a level of puerile avatar of social justice propaganda in recent years is their distance from characters of his precise mold. Superheroes are so caught up in dispensing social justice defined by a subjective morality revolving around group identities and collectivist ideologies that they divide people across racial, sexual, and party lines rather than unite them under a common, fixed morality. They’re too busy apologizing to disaffected groups and minorities to encourage any sense of confidence and moral certitude. What they’ve forgotten is that the central concept of the superhero is one of individualism. The concept of one man or woman of exceptional ability using his or her talents to better a community, protect the innocent, and punish the guilty while expecting no reward in return stands in stark contrast to the collectivist ideologies that focus on shallow, external qualifiers like race, gender, or sexual preference to determine whether a person either deserves to receive or dish out justice. Today’s heroes aren’t about justice, but about power and political influence (though they like to define those things as justice), and they demand of others rather than selflessly give of themselves.

Those of us who pine for the morally binary heroes of old may find a great example in Solomon Kane. He wanders the earth righting all wrongs, protecting and avenging the weak, and punishing the guilty regardless of their personal, social, racial, or religious standing, and what’s more, he not only expects no reward, but adamantly refuses to be put on a pedestal or accept power, wealth, or worship. He rebukes such offerings and goes his way as soon as he’s done his good deed. He has no use for praise and never presents himself as anything other than a humble servant of God, often downplaying his own exploits to others.

“‘I came here,’ said Kane simply, but what a world of courage and effort was symbolized by that phrase! A long, red trail, black shadows and crimson shadows weaving a devil’s dance—marked by flashing swords and the smoke of battle—by faltering words falling like little drops of blood from the lips of dying men. Not consciously a dramatic man, certainly, was Solomon Kane. He told his tale in the same manner in which he had overcome terrific obstacles—coldly, briefly and without heroics.”-

-‘The Moon of Skulls’, Howard

While Solomon Kane has inspired a plethora of dour dressed scions for almost a century, many such characters are but shallow, cosmetic copies of the character in question. While many retain the same darksome, world-weary characteristics, swashbuckling aesthetic, and ghostbusting, monster hunting elements of Kane, many of their creators see this outward persona as an explicit expression of a trite, overdone expression of grey morality and use it to populate pop culture with a slew of interchangeable, whiny, emo antiheroes slaying monsters and taking time out to cry about the failures of a conventional, traditionalist moral code and how ‘the real monster is humanity’ as if that hasn’t been overdone since the 60s. Those people miss the point by a long shot.

Solomon Kane is as morally binary a hero as anyone could possibly conceive, and his black, puritanical garb emphasize it almost as much as his own words and actions. He’s a black and white character without a speck of grey on him. The savage tales of this pulp avenger are the adventures of a white night in a grey world—a light of courage and hope in a dark age. He doesn’t encourage men to stay the course and give in to their demons because the world is a cruel and dark place. Instead, he embodies the commandment of Christ to take up our Cross and follow Him. Like all Christians, Kane has no idea what God’s plan is for Him nor whether his actions will have a broader, lasting impact on the world. Yet he continued unabated in his mission with only his faith to guide him, trusting God to guide his every step. Kane affirms his faith in God’s wisdom and providence in the final pages of ‘The Moon of Skulls’ when he delivers a sermon to Marilyn, the young girl he' rescued from the vampire Queen Nakari. In the midst of this sermon, towering over the remains of a crumbling and decadent civilization, he assures her,

“Think you that having led me this far, and accomplished such wonders, the Power will strike us down? Nay! Evil flourishes and rules in the cities of men and the waste places of the world, but anon the great giant that is God rises and smites for the righteous, and they lay faith on him.”-

-‘The Moon of Skulls’, Howard

This is the message of Kane—to be not conformed to the ways of this world, to stand up straight with our shoulders back and face whatever storms life throws at us, to wage our war as Ephesians 6:12 says,

“…against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of darkness of this age, against spiritual hosts of wickedness in the heavenly places.”

To not fear, to take up your cross and follow Christ, to maintain your faith and courage in the face of all adversity, to face any danger in the pursuit of justice, to defend the innocent and punish the guilty—this is the message, the gospel of Solomon Kane. The fact that we let such a hero of western fiction fade into obscurity speaks volumes as to the state of our culture and the degradation of our values under the yoke of moral relativism and social justice.

So let us reject modernity, embrace tradition, embrace heroism, and give our heroes higher goals to fight for. Let Kane’s crusade not be in vain!

For anyone interested, I made a revised and slightly expanded version of this essay. Let me know if you think it's better.

https://open.substack.com/pub/austinboucher/p/the-savage-tales-of-solomon-kane-f62?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=1raal1